As you may know, ice exists in many forms. In its solid state it appears stationary, but in fact ice is naturally in motion. In this first edition of Frozen Fun Facts by guest editor Quinn Wenning, we take a look at the range of ice speeds, both terrestrial and ice forms that are completely out of this world.

By Quinn Wenning, Postdoctoral researcher, Earth Sciences, ETH Zurich

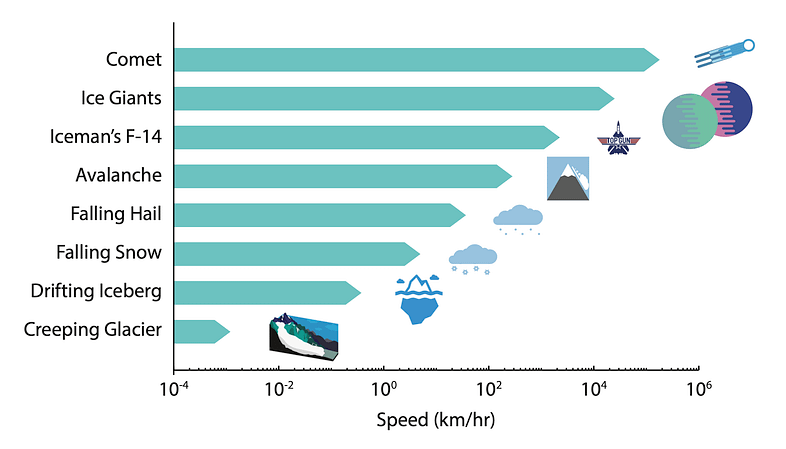

Can you spot the odd duck in this trend? Hint: it’s not Iceman’s F-14. Figure by Q. Wenning.

The mission at Recogn.ice focuses on ice that occurs on Earth, but ice is also abundant in our solar system and across the many galaxies. First on the list of speedy ice forms are Comets, small solar system bodies that are mostly made up of ice. These frozen H2O masses have been clocked in at speeds of over 175,000 km/hr, making them one of the fastest moving forms of ice in the universe! They are almost 10 times faster than the orbital speeds our solar system’s two Ice Giants, Uranus and Neptune, who revolve around the sun at around 24,000 km/hr.

Back on earth, ice gets around in many ways. It can move in rapid and abrupt movements like avalanches or extremely slow like creeping glaciers. When unstable snow and ice spontaneously collapse off mountain slopes, avalanches can rush down at speeds of over 300 km/hr. Here in Switzerland, these avalanches pose great risks for skiers and other mountain goers. This year has been especially snowy causing many avalanches across the Swiss alps. Next on the list are hail and snow: falling hail drops out of the sky at speeds of 40 km/hr, while snow generally falls ten times slower at around 5 km/hr. As ice accumulates and forms larger masses, the speeds decrease. Icebergs, who float around driven by currents in frigid oceans generally move at speeds of 0.36 km/hr. But Ii you think that’s slow, think again. In its slowest form, glaciers creep down mountain slopes at agonizingly slow speeds. Jakobshavn Isbrae, a giant Greenlandic glacier, is considered to be the world’s fastest, but it moves sluggishly in comparison at only 0.001 km/hr. Calling it a snail’s pace would be a slight to the garden creature, who actually moves about ten times faster than Jakobshavn Isbrae.

To visualise the speed differences, we must compare the speeds in a logarithmic scale. From comets down to drifting icebergs, the graph shows an exponentially linear decreasing trend, where each step is approximately 10 times slower. ‘Iceman’ flying in his F-14 Tomcat in the 1980’s film Top Gun, who’s ice in his veins flying style, bridges the speed-scale between terrestrial and extraterrestrial ice forms. Down at the bottom, fast glaciers cannot keep up with its other frozen friends, peaking about 100 times slower than the next slowest ice form. And then we haven’t even mentioned the speed of glaciers closer to home yet… The Great Aletsch Glacier, the largest glacier of Switzerland and the European Alps, covers up to a staggering 0.000023 km/hr. Call it leisurely, or should we say gleisurely.